To the lay person, menstruation is a basic biological function for a woman, and thus her personal problem! That is mostly where the understanding begins and ends. But this deeply taboo issue has many impacts, which are still not, part of the bigger discourse. This story touches upon some dimensions of how menstruation can be a monthly disaster for women who are still invisible to the larger world.

Menstruation and sanitation

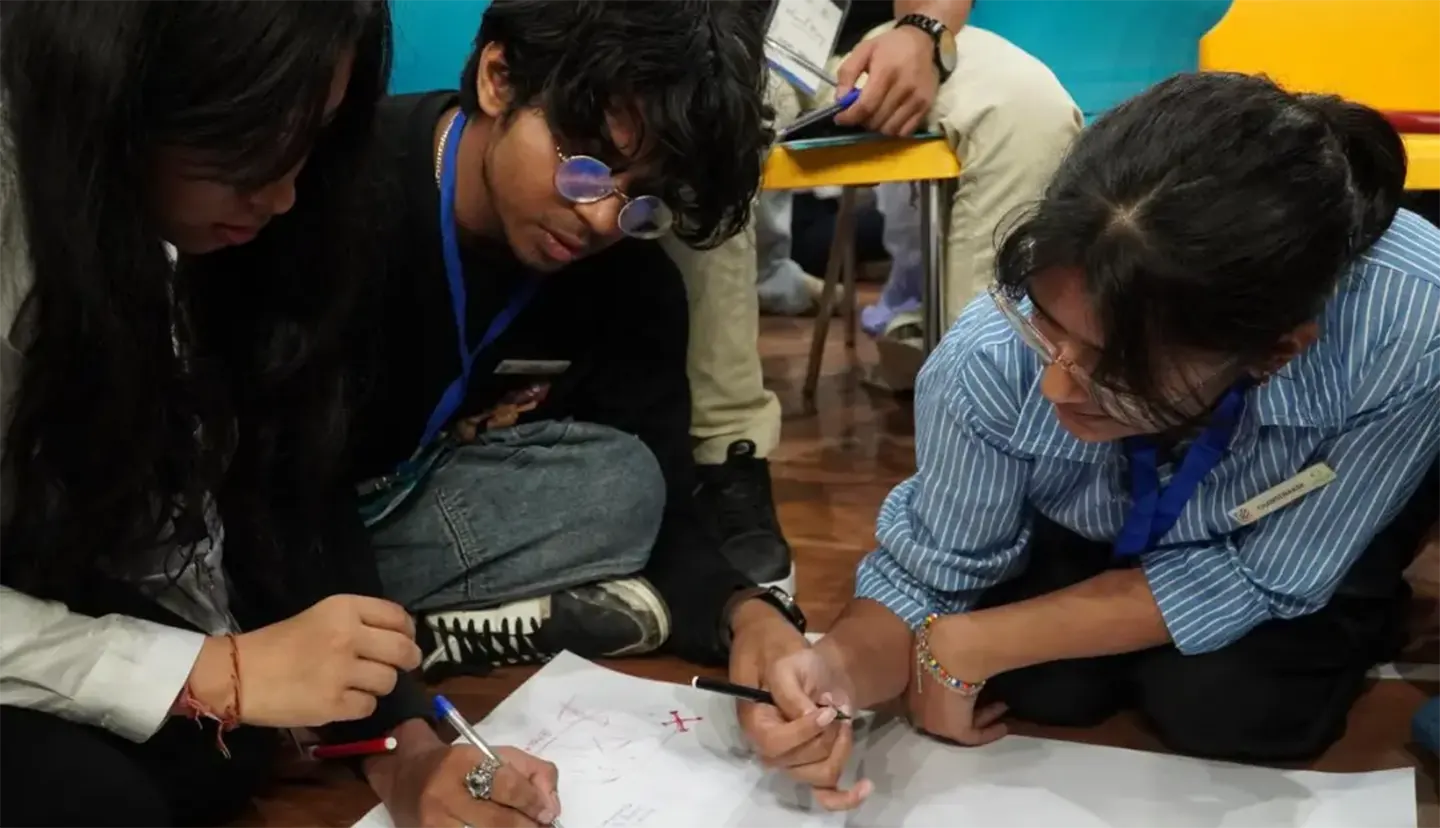

Sanitation and the menstrual health and hygiene of women are closely connected. At a NJPC session on menstrual issues, a group of 30 tribal women from Masora Kala village (Lalitpur district, Bundelkhand, UP) spoke about the lack of private bathing spaces. The single hand pump situated besides the road forces them to take a bath in the open. When our Goonj team motivated them to take action they built a community bathroom to ensure their dignity. Under Goonj’s Not Just a Piece of Cloth (NJPC) campaign our work closely juxtaposes sanitation and menstrual issues among women.

In Sahi village Daringbadi district, Odisha, the women used to bathe in the open at the roadside earlier. They had to wash their menstrual cloth in the open. It is not difficult to imagine that the hurriedly washed cloth carried infection and also the place became consistently unhygienic for other women to use. This open bathing area, called Chua or Duckwell, was also being used by the animals. With reference to the newly constructed covered bathing area made with tarpaulin, a woman from the colony said, “We knew nothing about our personal hygiene during our menses, but now we know.” A separate place, 20 metres away from this bathroom, was also dug up for the animals to drink water.

Menstruation and Women’s Health

In the upper parts of Guptkashi, Uttarakhand, where they don’t even have a gynaecologist available for deliveries or other emergencies, the question about what women do when they have menstrual cramps is entirely rhetorical. In the deep interiors of the Sunderbans, West Bengal, where cyclones and storms make daily life a challenge, the question about whether a UTI infection will or will not lead to cervical cancer is again a needless one. But what about the places, which have primary health centres, clinics, dispensaries, and hospitals? Are women with menstrual health issues treated more seriously in the health facilities across our country?

Quoting here a paragraph from a 2013 International Report by the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC), “The medical profession may not always be a source of good information either, as one participant suggested, when he pointed out that many junior doctors are not trained properly in menstrual hygiene management, even while they must deal with the medical consequences.”

In an NJPC session in an organization working with cancer patients our Goonj team met with a group of 50 women and girls recently. These included staff, front-line workers, cancer survivors, and teachers who shared their views on menstruation. One cancer survivor said, “I started menstruating whenI was 12 years but my menstrual cycle was not regular. I never told my mother about this. One day, due to heavy blood loss, I was admitted in the emergency room where I was diagnosed with uterus cancer. I was operated upon, my uterus was removed, so now I don’t menstruate.” Most women agreed that due to ignorance about menstruation young girls and women don’t pay attention to their menstrual issues. These issues where definite irregularities are manifest are and are ignored or hidden, can slowly take the form of uterine cancer, which can be fatal if not treated in time.

Dinabandhu, Head of KZSVS an Odisha-based partner organization of Goonj says, “The local ANM (Auxiliary Nurse Mid-wife) comes once a week just for giving vaccinations. Even she doesn’t have knowledge about menstrual health and hygiene. So there is no way of changing their knowledge and practices and hence they follow the primitive methods.”There are no health facilities nearby; the nearest District Health Centre in Phulwani, is 130 km away, reachable by a single bus plying on this route.

The big step forward: There needs to be a paradigm shift in the orientation of our health system and infrastructure where women’s menstrual issues are prioritized comprehensively. Even today, all across the rural and urban health system, the common response to a menstrual issue is ‘this happens’. An ecosystem is needed that will give a woman a safe space and opportunity to speak about these challenges. This will have a positive influence on her mindset and give her the confidence to approach the available health facilities without shame or embarrassment.

Menstruation and Drought

With only three running hand pumps for the entire village of Sudor in Panna District in Madhya Pradesh, water is a precious commodity. Women go long distances to fetch water on bullock cart or on cycles or carry the utensils on their heads.

“आधासमयतोपानीलानेमेंलगजाताहै, फिरमजदूरीभीकरोl हमनेतोगर्भवतीअवस्थामेंभीमजदूरीकीहैl माहवारीकेसमयदर्दइतनाहोताहैकिघरआकरपहलेंअपनेआपकोसेकतेहैं, फिरखानाबनातेहैं l” (Half of our time is spent in bringing water and then we have to go out to work as well.We have worked as daily labourers even when pregnant. During menstruation the pain is so much that when we come home, first we have to do hot fermentation before we can cook food.)

Drought is not as visible as other disasters such as earthquakes or cyclones, yet the devastation is equally lethal. Women face the brunt of it because typically, the men migrate to the cities leaving behind the ever-growing responsibility of running the household, to their women. The choices and priorities for these women are extremely limited, sometimes bordering on the fight for mere survival. Under such circumstances their menstrual need and hygiene is not even a priority.

Apart from Goonj’s larger work for drought-hit communities, reaching out more cloth to them ensures that these women have excess cloth in future as well, for their personal need.

Menstruation and Disability

The silence in a classroom full of 35 bubbly girls only amplified that they were hearing and speech impaired; their frantic hand gestures showed that a spirited discussion was in progress on the subject of menstruation. The girls were taking part in Goonj’s NJPC session. The teacher explained the issue of menstrual health and hygiene to them and asked them to fill the NJPC — A Million Voices form.

Given the strong taboos and challenges that adolescent girls and women generally face around menstruation, the problem gets escalated manifold for the disabled. We have another story in this book, on how Goonj’s work was replicated at Anandwan, Baba Amte’s exemplary work with the leprosy afflicted. This was the time when Anshu Gupta, Founder Goonj, had pointed out to Pallavi Amte, Baba Amte’s grand-daughter-in-law of how NJPC could address the needs of the leprosy-afflicted and of people with other disabilities living in Anandwan. One of the insights that emerged was about the visually-challenged girls at Anandwan who didn’t find out, till someone told them, about their periods. Even using a ready-made sanitary pad presented practical difficulties for these girls. Pallavisaid, “Our focus was primarily the leprosy afflicted but Anandwan also houses people with many other disabilities and we wanted to pay more attention to their specific needs as well. We have here more than 350 disabled girls and women in their reproductive age but we hadn’t thought about their monthly needs of menstruation. Goonj’s NJPC initiative enabled us to think in this regard. A well-oriented warden now takes special care of these girls, providing them information about menstruation and other reproductive health related issues.”

Menstruation and migrant women

According to the 2001 Census, out of the 309 million migrants, female migrants constitute 218 million while only 91 million are male. These women work in the tough terrains of mountains, on the roads of metros, and in the agricultural fields of different states. Invariably, they neither have access to basic facilities such as toilets, nor can they afford the ready-made sanitary pads besides the fact that they know very little about menstrual health and hygiene.

We work in a big way with migrant labourers in the most difficult terrains like the groups working with the BRO (Border Road Organization), making roads on the highest altitudes in extreme temperatures. In Jammu and Kashmir, after the massive floods in 2014 migrant labourers and their families were one of Goonj’s focus groups for relief and long-term rehabilitation work. Hailing from Bihar, West Bengal and other areas, these people were the worst sufferers, without any security, shelter, or attention from the agencies. The scenario unfortunately is not very different in the slums of urban and semi-urban areas. In 2015, our Goonj team started working deeper in Delhi-NCR, connecting with organizations working with different communities of women and adolescent girls. The objective was simple — to give the women the much-needed space to share their challenges around menstruation and to sensitize them about menstrual hygiene. In the NJPC, chuppi todo baithaks (break the silence meetings), many insights emerged from women engaged as domestic workers, sex workers, waste pickers, and adolescent girls. The story is the same for migrants in any part of the country; basic sanitary facilities and health system around menses and otherwise is largely missing.

Sadly, women are the most marginalized even among the most ignored communities such as landless labourers, leprosy patients, homeless migrants, disabled people, etc. That is what makes our work most fulfilling and meaningful. These are the women who strengthen our resolve to create a space for the voiceless to speak up and make the world understand that it is a human issue not a women issue!!