What if the poverty we see isn’t just about money, but about access? Every year, millions go without basic clothing, while millions of tonnes of usable fabric end up in landfills. How do we bridge this paradox?

On a cold winter night, people try to sleep in a makeshift shelter, lacking a warm blanket over their numb bodies. A child hesitates to attend school because the only pair of shoes has torn beyond repair. While poverty is often measured in financial terms, what about the silent struggles—those that are not counted in statistics but define everyday survival?

India’s poverty metrics define a person earning less than ₹972 per month in rural areas and ₹1,407 per month in urban areas as below the poverty line. However, poverty extends far beyond income levels. The paradigm of poverty assessments considers education, health, and living standards, but they overlook material deprivation—the absence of essential goods like clothing, footwear, household items, and hygiene products.

Even when financial resources exist, systemic barriers, infrastructural gaps, social inequalities, and inefficient distribution prevent access to these vital materials. This gap in national poverty assessments underscores the need for a broader understanding of deprivation—one that recognizes material poverty as a critical aspect of human well-being.

The Hidden Cost of Throwaway Culture: Surplus and Sustainability

While millions struggle with material scarcity, our world paradoxically overflows with surplus. The linear economy—based on a ‘produce-consume-dispose’ model—accelerates waste generation. Clothes that no longer fit, school supplies replaced each year, and household items discarded for newer versions all end up in landfills, even when they are still useful.

India generates approximately 62 million tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) annually, with an estimated 31 million tonnes ending up in landfills. Of this, nearly 15 million tonnes are recyclable, yet much of it remains unutilized due to inefficiencies in waste management. Right now, India’s landfills stretch across 10,000 hectares—overflowing with things we could have reused. Instead, they are creating environmental and health hazards we can no longer ignore

- Methane Emissions: 84x more potent than CO₂.

- Toxic Runoff: Mercury & ammonia poison groundwater.

- Lost Potential: 15 million tonnes of recyclable materials wasted.

This wasteful cycle deepens both social inequality and ecological crises. Usable materials are discarded while millions go without necessities. The failure to recognize the extended life cycle of materials results in resource wastage, pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss.

Landfills, Climate Change, and the Human Cost: A Growing Crisis

Landfills are not just spaces for discarded items—they are sources of environmental devastation. Decomposing waste releases methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Toxic substances like mercury and ammonia leach into water sources, depleting oxygen levels and creating “dead zones” where marine life cannot survive.

This crisis is not isolated; climate experts emphasize that only by addressing waste, poverty, and environmental issues as interconnected challenges can we develop sustainable solutions.

The Circular Economy: Sustainable Solutions with Goonj

The stark contrast between surplus and scarcity demands a shift toward a circular economy—one that extends the life cycle of materials and reintegrates them into communities that need them. The Japanese philosophy of Wu Wei—often interpreted as “the art of doing nothing”—actually means “doing nothing against nature.” In today’s world, the conventional model of development makes little effort to stay grounded and listen to the needs of people who are deeply connected to jal, jangal, and zameen (water, forest, and land). For over 26 years, Goonj’s approach has connected urban surplus with rural needs, transforming underutilized material into resources and fostering dignified development, resilience, sustainability, and social equity.

Bridging the Gap: From Cities to Villages

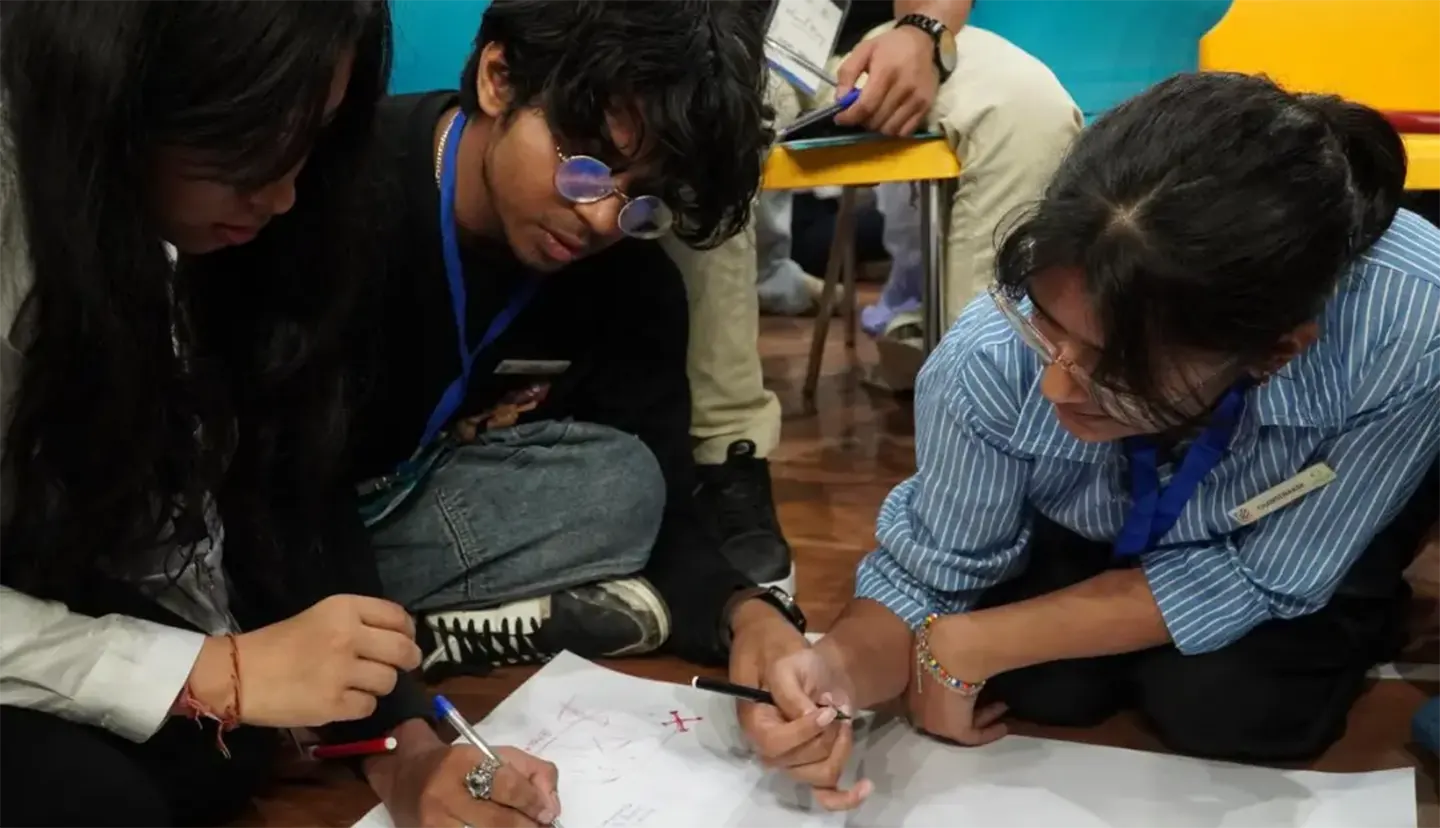

In the last 26 years Goonj’s work has grown in India; from underlining the basic but often neglected need of cloth for the most marginalised while a vast majority in the big metros were buying and discarding clothes at alarming rates. The large-scale work of Goonj across India is a testament to how urban underutilised material, especially cloth can be turned into rural assets. Goonj turns almost any underutilised materials—from textiles to household items—into catalysts for change. It has created millions of cloth sanitary pads out of India’s by transforming India’s pre and post consumer textile surplus into affordable, reusable cloth pads for rural marginalised women . Rather than simply distributing these pads as charity, Goonj instead uses these pads to nudge conversations about menstrual wellbeing among rural women and uses these pads to mobilise women to take collective local action against their menstrual issues. Thus repurposed surplus cloth encourages women to talk about and prioritize their health, fostering behavioral change.

Goonj also uses underutilised material, including cloth, to nudge rural communities to take action against their diverse local development issues, like water, sanitation, education, menstrual health, access etc. A powerful example of this is seen in Kalitala, where under Goonj’s ‘Cloth for Work’ initiative people of the village used scattered local debris into creating a critical infrastructure for themselves, enabling the community to rebuild in the aftermath of a disaster. The participants in this work received material Kits as a reward for their efforts and wisdom.

Kalitala’s Story: Community-Led Climate Action

Kalitala, a remote village in the Sundarbans, exemplifies both the struggles of climate change and the power of resourcefulness. In 2009, Cyclone Aila devastated the region, flooding fields, eroding homes, and cutting off entire communities from essential services.

Truckloads of cloth in Chennai after the 2005 Tsunami

When the Goonj team arrived, we saw a community rebuilding from within, but without external support. The villagers of Kalitala, realizing the urgency of reconnecting their village, collected scattered bricks and, through Goonj’s Cloth for Work (CFW) initiative, constructed a 1.5 km motorable road. This road now connects them to healthcare, education, and markets—fundamental elements for long-term resilience.

Mangrove saplings planted by Kalitala villagers to create a natural shield against cyclones and floods.

“In a disaster-prone area like ours, high tides are a regular phenomenon. This mangrove wall is our only shield from disasters,” says Thakur Das Burman, a resident of Kalitala.

As part of post-disaster rehabilitation, in 2011, 60–70 villagers planted mangrove saplings in the most vulnerable areas of Kalitala. Three years later, those saplings had flourished into a dense 100,000 sq. ft. mangrove forest. Today, these trees serve as a natural protector against cyclones, flooding, and coastal erosion—offering not just ecological protection but also securing livelihoods for generations to come.

They planted a saviour for the coming generations

Take Action: Work for a Sustainable Future

Combating material poverty and ecological degradation requires collective action. A circular economy is not just an alternative model—it is a necessity. The economy and the ecosystem must work in harmony. Right now the narrative of material circularity has been largely technological innovation driven, oriented with a scarcity mindset.

We invite you to be a part of this shift. Start where you are—whether by setting up a Goonj kee Gullak, joining Team 5000, organizing a collection drive, volunteering, interning, or simply subscribing to our monthly newsletter. Every small action contributes to a larger movement. Visit www.goonj.org to learn more or write to [email protected].

Many options, but the choice is always one: Taking Action.

References-

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2023. “Article Title.” PubMed Central

Ghimire, Mahadevia, Kanksha Vikas, and M. Vikas. 2012. “Climate Change – Impact on the Sundarbans: A Case Study.” International Scientific Journal 2: 7–15.