Today, a discussion and debate is raging about the veracity and effects of the various sanitary pads available in the cities and in the villages of India. One thing is clear that many people still have doubts that cloth can be a big option for the masses.

This story sheds light on the environment disaster around menstruation right in our midst, in the cities. Allowing this same scenario to repeat itself in the villages of India will be something that all of us working in this field will have to be accountable for in time to come. It is important to share the story of cloth and menstruation here.

There is no official data on menstrual waste in India, but on an average a woman is said to have over 3,000 days of menstruation. There are about 300 million menstruating women in India, and as per some surveys hardly 10 to 12 per cent of them have access to or can afford sanitary napkins. Even if we take 10 to 12 pads as a woman’s monthly consumption per month it is almost a million kilogrammes of waste that is being generated even today. And we all know this is mostly non-biodegradable product. No one is taking responsibility of the disposal of this waste.

These numbers are a staggering reality check on what is already happening in our cities. In the Indian feminine hygiene market the sanitary napkin segment is one of the highest revenue-generating products. This is obviously going to grow with time, indicating the huge potential and excellent profit margin for the manufacturers of plastic-based sanitary napkins.

Now that menstrual hygiene and management is becoming an issue, the over-reaching well-intentioned hope is that more women and girls will have access to the products. When we generate a million kg of non-biodegradable waste just with 10 per cent female population utilizing sanitary pads, imagine what will happen when the demand and consumption goes up by just a few percentage points, if there are no alternatives present!

Therefore,until there is a mass-market, biodegradable,sanitary napkin available, the present non-biodegradable one with a plastic sheet in the pad and the plastic wrapping essentially means another environmental mess in the villages as well. Why? Doing even “a back of an envelope” most basic rough calculation, let us assume that a village has around 200 to 400 houses with approximately 1000 women using sanitary pads. Each woman needs at least 10-12 pads every month, which means approximately 10,000 pads every month or over a hundred thousand per annum. This is just one village. Even if we marginallychange the assumptions, the results are staggering. A non-biodegradable product in a village, which has no proper sanitation and disposal facilities, means disposal either by burning or by discarding near a water body or in a field. The burning would pollute the environment and the discarded plastic will end up going into the soil or water, which is already worsened due to fertilizers and pesticides (it takes about 500 years for a plastic in a pad to degrade). The waste disposal infrastructure in cities is already overloaded. In a city slum we would be walking on sanitary pads as most toilets would be choked without a separate channel to dispose. The waste-pickers are already getting the worst of it with millions of pads a month to be handled, turning it into a huge environment and health hazard. The jury is still out on solutions such as incinerators because some reports highlight their dangerous environmental and health impacts. The growing urbanization, a middle class with better income levels, rising awareness of and exposure to media, growing number of working women, and the increasing availability of sanitary napkins is only going to add to this mess.

The policy makers and stakeholders have a big responsibility here, to ensure that in trying to solve one problem they don’t create a new problem.

Goonj is trying to reach the women who are still outside the access or affordability map of disposable pads, using clean cotton cloth as a tool. Till date it has reached more than 40 lakh (4 million) MY Pads across India. More than 2 metres of shredded cloth is used to make a pack of 5 My Pads; that means that more than 8 lakh (eight hundred thousand) metres of discarded cloth has been put to use. This is the cotton cloth from the cities — bed sheets, salwar-kameezes (traditional north Indian dress of women), cotton t-shirts, and so on,that the cities out-grow, discard, and give away. Tons of cloth flows in from all over India to make this model efficient and sustainable. If this entire quantum of cloth was purchased from the market at the present rate (of approximately Rs. 50 per metre) it would cost Rs. 4 crores (Rs. 40 million) just for the raw material! That would escalate the cost of the pads ten-fold, making these pads unaffordable for the women in the most far-flung areas.

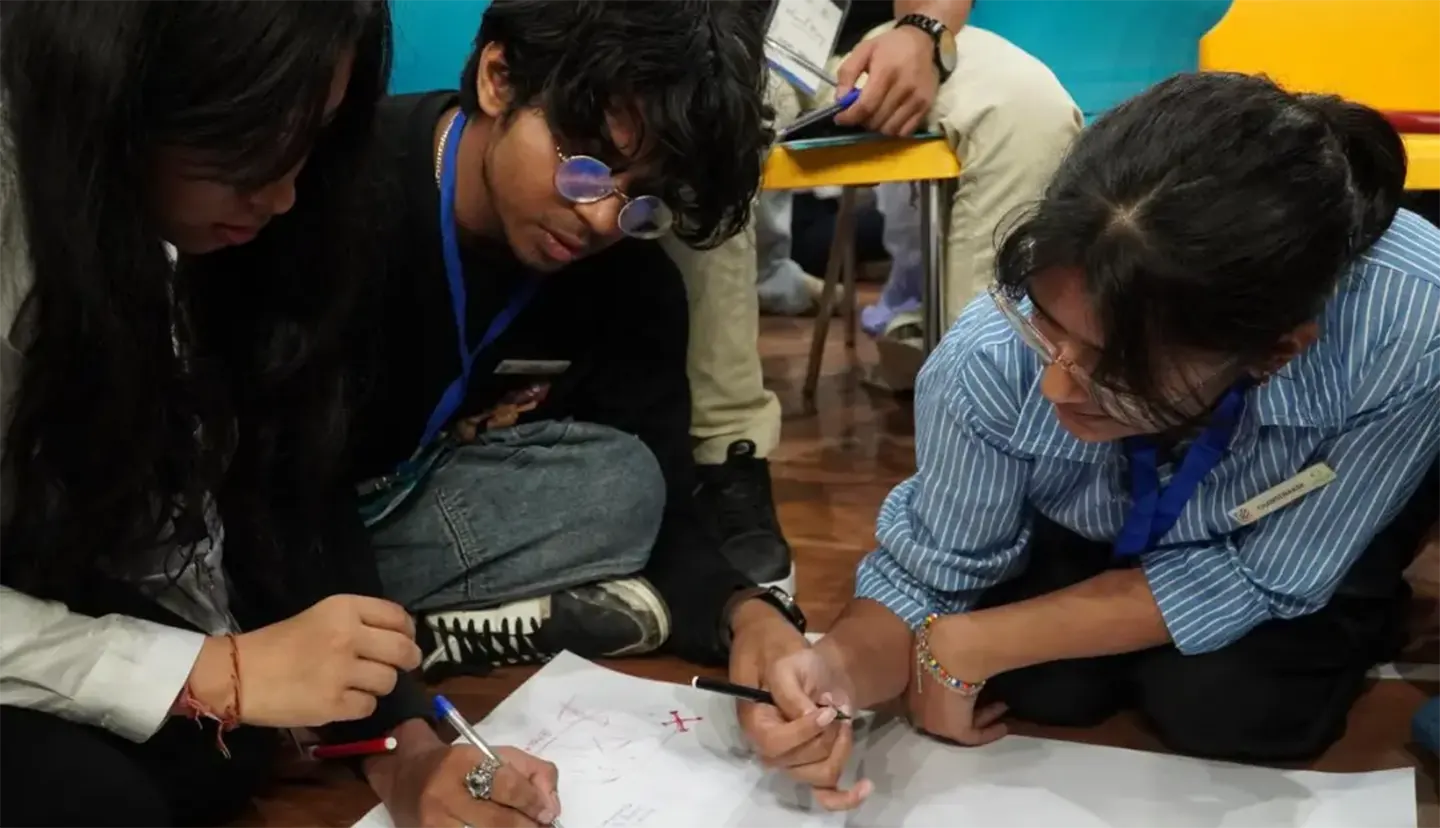

So what do all these dizzying numbers mean? Probably that for millions of women cloth is still a viable option instead of the plastic-clad sanitary pads. Meanwhile, we need to look out for and nurture many more affordable and environment-friendly options. Goonj’s Not Just a Piece of Cloth (NJPC) initiative is successful because of the cloth given by the masses. What makes it more powerful is when Goonj uses the MY Pad as a tool to open up discussions on the issue, breaking the culture of shame and silence around it and spreads awareness about the related health and hygiene issues among women who are unaware.

The big learning is that the Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) story runs parallel to the sanitation story in this country and therefore the ecosystem of one affects the realities of the other. All of us especially the ones working in any way in the MHM space, need to look carefully; not only at the products we use and promote but also the infrastructure and regulations we have and want to build around menstrual products. The sobering reality at the back of all this discussion is that many women still aren’t even able to share their menstrual challenges with the world.

Can we please allow a woman to be a human being, equal in all ways?